Prior to releasing the RFP, procurement groups should finalize which organizations are participating in the RFP, if more organizations will be able to join after the RFP’s release, and how obligated buyers will be able to follow through on their individual purchases if a project is selected by the group.

As group participants make their respective pitches to senior leaders, the group should establish which organizations are moving forward and finalize each participant’s desired amount of energy. The group may also choose to invite additional buyers to join the effort if they agree to the established RFP terms. Procurement groups that make significant changes to their membership may want to update or sign a new governance document prior to issuing an RFP that outlines who is involved, how the RFP will be managed, and who will select the project.

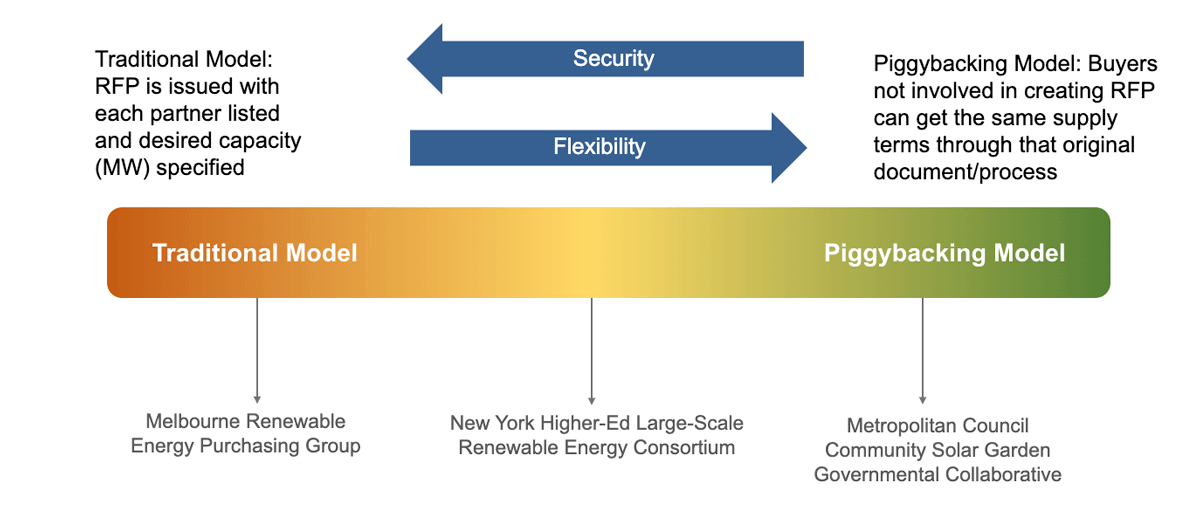

This is a decision point where the group needs to finalize the governance structure, which will decide whether other buyers can be invited to join or “piggyback” on the deal after the RFP is issued. Under a traditional approach, participation in the eventual transaction is restricted to partners that participate in the RFP, with each organization specifying its desired amount of electricity. With a piggybacking model, buyers not involved in the RFP can join the project later and get the same supply terms as those listed on the RFP. A related question groups should consider is whether individual buyers will be obligated to move forward with their purchase if the group ultimately selects a project.

While piggybacking and minimal commitments can provide attractive flexibility, such approaches can also have significant downsides. In particular, the more flexibility participants retain, the less able developers will be to make firm, competitive offers or even provide a response at all. As such, procurement group partners should consult with potential respondents to find the right balance for their context and needs and, potentially, come up with creative solutions.

The video below introduces the differences between these two governance structure models with the case studies of the Melbourne Renewable Energy Project, the New York Higher Education Consortium, and the Metropolitan Council Community Solar Subscriber Collaborative.